San Giovenale

- a 2500-year old wine tradition

On the Italian peninsula, the Etruscans in the north and the Greek colonizers in the south, cultivated vine. The knowledge to ferment carbohydrates to ethanol, that is the process of altering grape must into the alcoholic beverage of wine, was spread from the East. The production can be traced 8000 years back in time to southern Caucasus and specific cultivation techniques, practices and religious ceremonies have since then been developed by the various cultures that adopted it.

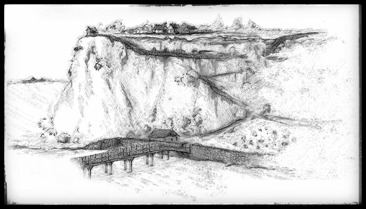

Still today the Etruscan word for wine − vinum − can be found in place-names such as Vignolo or Vignale. These names hint of timeless and suitable places for wine production. At the Etruscan site of San Giovenale, 80 km northwest of Rome, the predominant plateau south of the acropolis is in fact called Vignale. Since archaic times the site has been widely used for viticulture. The adjacent drawing shows an interpretation of Vignale's ancient slopes, where the Etruscans initially harvested and pressed the wild grapes, vitis sylvestris, in the surrounding deep ravines. As can be seen in the photo below, lianas of vine are still to be found near the site. This was the mystical environment where you could expect to encounter Fufluns, the wine god himself. In later periods, as we shall see, cultivation was transferred to the top of the plateau and this became the introduction of the modern vineyards we encounter today.

The Vignale plateau is today covered with vine plantations, olive grooves and orchards. Photo: The Vignale Aerial/Archaeological Project, VAAP.

The Vignale plateau is today covered with vine plantations, olive grooves and orchards. Photo: The Vignale Aerial/Archaeological Project, VAAP.

Our knowledge of the Etruscans’ relation to their precious wine is based on archaeological remains such as pictorial vase motifs, terracotta plaques and various inscriptions. However, the most detailed sources to viticulture and the traditions around wine, largely comes from the ancient writers. The latter comprise Roman authors such as Cato, Varro, Columella and Pliny, who themselves were viticulturists. During ancient times wine was compared with a vital force − vita vinum est − and together with wheat and olive oil it was considered as one of the three staple commodities. Besides being a valued beverage spiced with honey and herbs, wine could moreover be transformed into vinegar. It was also a common remedy for various illnesses. For example, the leaves and the shoots could be mixed with pearl barley to cure headache and fever. When boiled down, the must defrutum, was used for semi-preservation of fruits and vegetables.

The aristocratic families could afford to cultivate the vines and to drink the fermented grape must, but their hard working slaves that were engaged in the wine production, had to content themselves with posca. This mixture called lora, contained grape skins and stems fermented in water and vinegar.

When Theopompos, the 4th century BC Greek rhetorician, fantasized about Etruscan women he commented on them as being “expert drinkers”. This stood in sharp contrast to the Roman women who initially were prohibited to drink wine and punished when so happened.

From wild grapes to tasteful wines

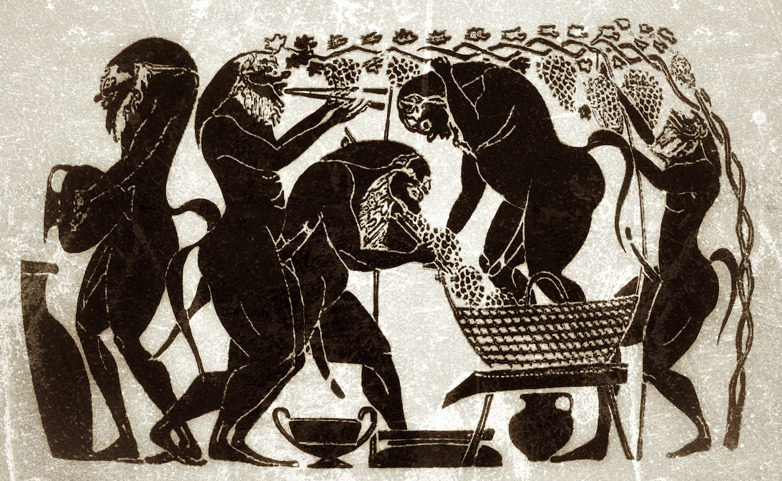

The wild grapes grew like lianas, twining the trunks up into the treetops. Thus, it is not surprising to find depictions on vases showing how workers had to climb high to harvest the grapes. Pliny the Elder wrote how important it was to establish explicit insurance contracts between the viticulturist and the seasonal workers. These had to cover costs that may arise for injuries or possibly even funerary expenses. This harvesting method continued beside more controlled cultivation techniques and today we recognize this wine as labrusca.

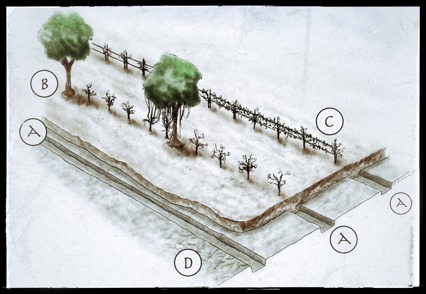

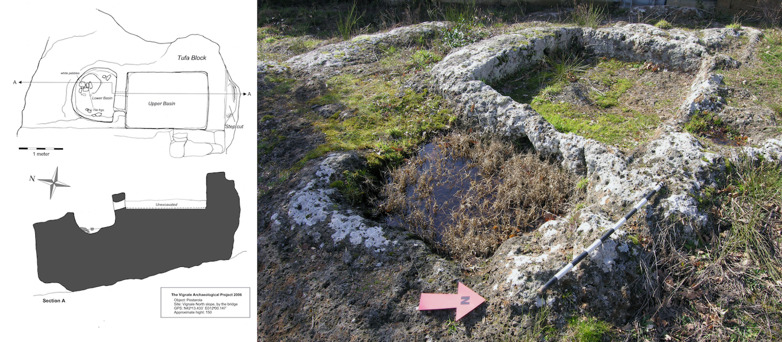

During the late Etruscan period it was common to allow the domesticated vine − vitis vinifera − that originated from the wild vine, to twirl around poplars and elm trees planted in slopes facing southeast. The vine stocks were then planted at equal intervals with trees as support or sometimes trained on stakes. The deep trenches cut into the tufa bedrock, on the Vignale plateau, bear witness of this Roman cultivation technique, which is utilized still today. Several possible viticulturists resided at San Giovenale; Urqena and Alsi are two of twelve noble family names inscribed on wine drinking cups found near Vignale.

From the middle of the first millennium BC, much of San Giovenale’s hinterland was probably owned by a gentility of local clan leaders who distributed right of properties within the territory. During Roman influence the area changed into scattered and medium sized farms, villae rusticae, of circa one hectare each.

The drawing above shows parallel cultivation trenches cut into the bedrock on the Vignale summit (A). This reconstruction of ancient cultivation techniques also illustrates how the vines were initially planted between supporting trees (B), or trained on stakes (C). Grooves in the bedrock, exposed during excavation, show traces of later farming with wooden plough (D).

The processes in the production chain transformed with time. From the early Etruscan period, depictions on vases show baskets and wooden pressing tables in use when harvesting grapes. Later, wooden barrels were employed for storing and transport – these and amphorae were coated and sealed with pine-resin in order to prevent the wine from turning bad if reacting with oxygen. The resin gave the wine a peculiar and appreciated taste - a phenomenon that became a tradition. This is why we still today can enjoy retsina wine.

Pliny the elder was particular interested in studying and classifying grapes and wines produced in Italy and abroad. The Italian wines were divided in 3-4 categories based on taste, soil and climate. He considered wines produced of the Aminean grapes in Campania and Nomentane, with the red stock, as quality wines. Pliny was particular fond of the Apian grapes (bee-wine) because they were adapted to a colder climate, but he considered the white grapes as the finest due to their sweetness. He mentioned Acilius Sthenelus, the son of a freedman from a farm northeast of Rome, as the best wine maker.

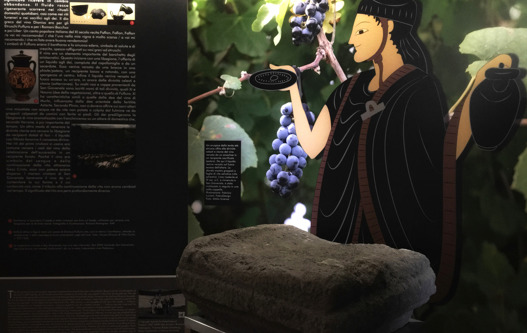

Often, a certain preservation technique gave the beverage a distinct character. In adding herbs, myrrh, honey and other resins, the taste could be affected in a favourable way. Amphorae were mostly customized for transport, whilst the larger dolia and pithoi were used for fermentation and storing. The latter were partly buried into the ground in order to keep a cool preserving temperature. The remains we find today derive from indestructible items such as pottery vessels and stone presses, pestarole. As can be seen in the illustration, these presses were cut into the bedrock and sometimes into free-standing blocks. Many of these were frequently utilized in Late Antiquity, during the Christian era, when wine became important within the Holy Communion. The late Etruscan altar, also present in the exhibition, had since long lost its original function when it was reused as a threshold in the Byzantine chapel of St. Juvenal. The latter who also gave the site of San Giovenale its current name.

Beverage of the gods

The life-giving forces of the gods required compensation to provide man with viability. Blood was the manifestation of life and in offering this, or the fertile bloodlike substance of wine, life was repaid in the form of abundance. The red fluid kept the generative machinery spinning through daily household rituals, funerary rites and sacrifices to the gods. For the Etruscans, the Greek god of wine Dionysos presented himself as Fufluns. Later they called him Bacchus and for the Romans he was Liber. In an Italian harvest chant from the 19th century, it was still possible to hear the words;

”…Fufluns, Fufluns! Grapes of my vineyard are scarce, I entrust myself to you for a better harvest…”.

Fufluns was the wine and his symbols were the kantharos, the winding ivy, health and growth − often portrayed on Greek and Etruscan vases. For instance, wine was an important part of the aristocracy’s banquets. These began with the head of the family, or a priest, performing a libation of wine to the gods – this was a ritual pouring of a liquid as an offering. A wine-jug was emptied into a phiale/patera, a bowl with a belly button in the centre. This was ultimately poured onto a glooming altar fire, honoring the celestial as well as the chthonic divinities that reigned “beneath the earth”. In the adjacent exhibition photo, a late Etruscan priest - haruspex - is seen performing this type of sacrifice. The backdrop shows grapes of the wild wine (vitis sylvestris) and the 4th century BC altar was excavated in San Giovenale.

In San Giovenale numerous Etruscan vessels and drinking cups are inscribed with deities such as Xi and Vesuna (vegetation goddesses) besides Fufluns himself. Xi shares similarities with the wine goddess from Murlo that was influenced by the eastern fertility deity Astarte. According to Pliny, wine mixed with water could not be presented to the gods on sacred altars. Neither did wine of untrimmed grapes, those struck by lightning or grapes trodden by men with soar feet. The gods preferred wine libation with a scent of frankincense, preferably from the household altar, which according to Varro was more important than the temple.

Another way of celebrating the chthonic gods was to pour a libation into vessels with a hole in the bottom - the drained liquid allowed for a divine acceptance. In the Early Christian church it was equally common to pour the remainder of the wine used in celebration of the Eucharist, into a perforated vessel. Since the wine symbolizes the blood and the continuation of life through Jesus Christ, wine cannot be discarded in the drain. When the Christian monks of San Giovenale drank wine from the chalice, neither the shape of the vessel, nor its content or the tribute to continuation of life had changed. The eschatology was quite different though.

The wine tradition continues on the slopes surrounding San Giovenale. Since 2005, San Giovenale Agricola, revives the old wine tradition, now with its celebrated red wine Habemus.

The Vignale Aerial/Archaeological Project

From the left: Richard Holmgren, Yvonne Backe Forsberg, Robin Fjellström and Hannu Kuisma, VAAP 2009

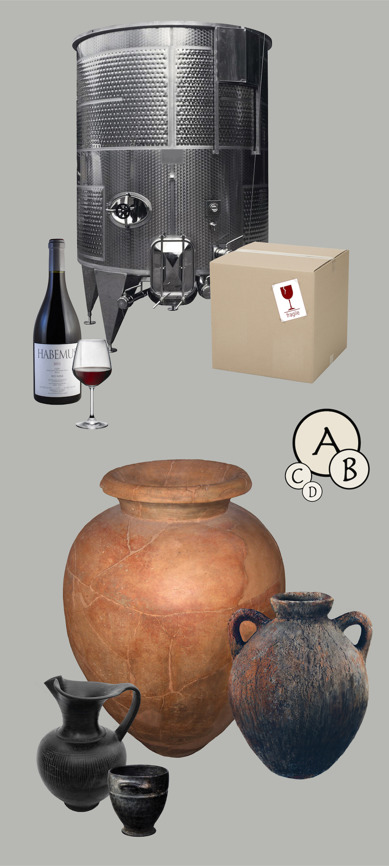

Wine containers - Now and Then

A comparison of modern and ancient vessels used in production and consumption of wine. One should note though that our modern wine bottle can function both as storage, transport, decanting and for some, even for drinking.

- fermentation/storage (A)

- transportation (B)

- decanting (C)

- drinking (D)